Buncha Hells

Gregory Kalliche

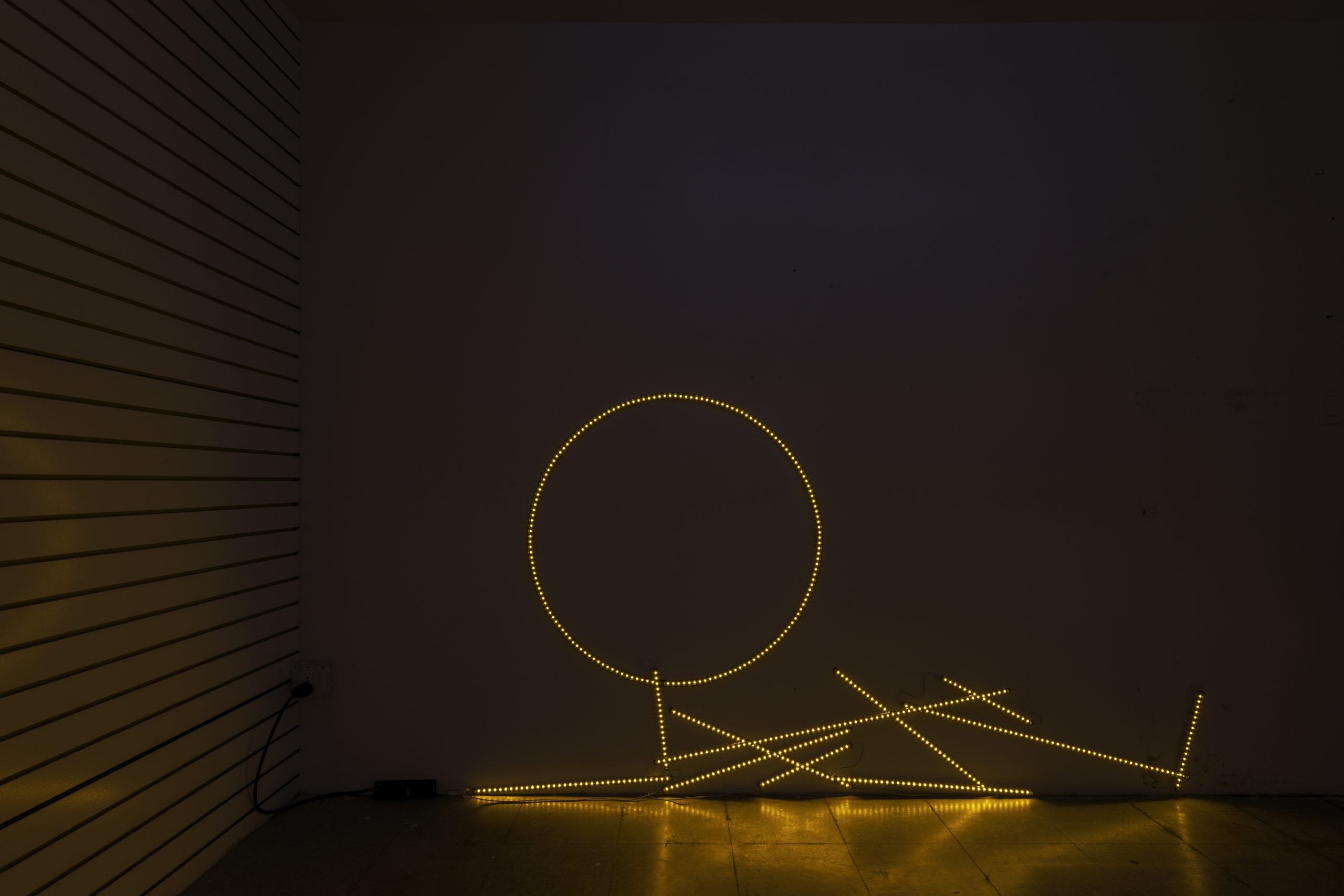

fell1

LEDs, aluminum channel, enamel on MDF, power supply, custom electronics, accompanying hardware

45 × 153 inches

2021

gnd gm

aluminum channel, enamel on MDF, power supply, custom electronics, accompanying hardware

42 × 181 inches

hot river

LEDs, aluminum channel, enamel on MDF, power supply, custom electronics, accompanying hardware

49.5 × 100 inches

2021

Abalus

LEDs, aluminum channel, enamel on steel, power supply, custom electronics, accompanying hardware

20 × 226 inches

2021

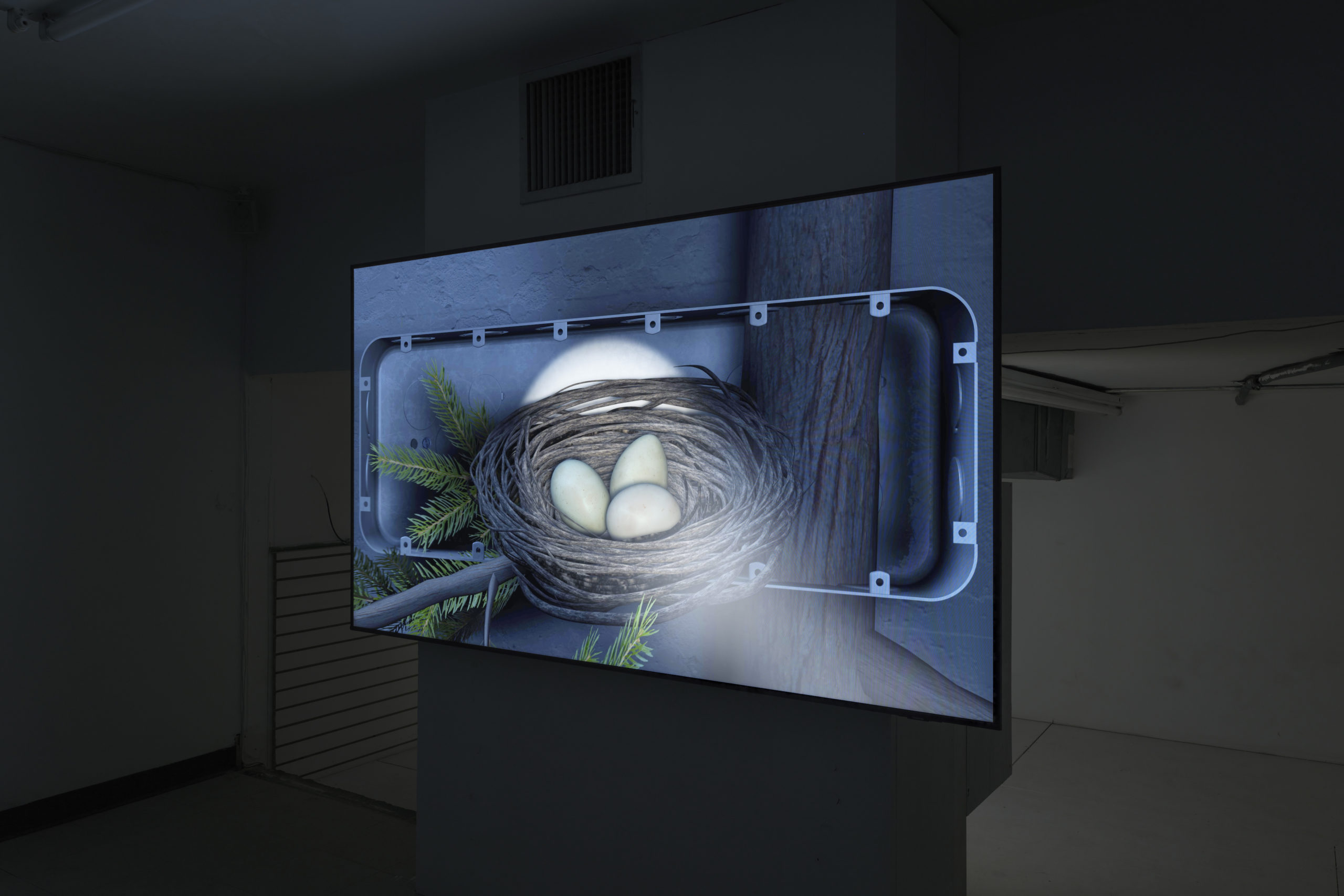

Buncha Hells

4 K video with sound

7 minutes 13 seconds

Buncha Hells Lighting Program

Eight channel lighting and electrical program, DMX controllers, lighting interface

2019

23 Oct–11 Dec 2021

Buncha Hells

Gregory Kalliche

Helena Anrather is pleased to present Buncha Hells, a new body of work from New York-based artist Gregory Kalliche. Developed over the last two years, this exhibition features a series of works that examine electricity as a point of research, subject matter and raw material. Taking place in a multi-roomed storefront at 6A Elizabeth Street, Kalliche has tapped into the infrastructure of the space elaborating on preexisting electrical and lighting components as well as adding his own. The result is an interconnected display of animation, light, and sound that unravels to a viewer as they move through the exhibition spaces.

Nowhere is the leaky relation between visualization and its comprehension more explicitly evident than in animation. As a representation and study of the “in-betweenness” of matter, animation is a temporal project—not the art of drawings that move but the art of movements that are drawn. As a field of study, animation is an inquiry constituted around the moments of transfer between life and the inanimate. And as a precursor to the newer expressions of modelled and rigged computer-generated flesh, it is the culmination of imaging strategies and histories which produce the aesthetic effects that we frequently and unconsciously watch in the world.

Cartoons take this notion of in-betweenness further: we understand the cartoon world order to be profoundly exaggerated and unachievable. To be destroyed and remain intact—this is the fundamental credo of the phantasmatic, cartoon universe. What cartoons depict, then, are visualizations of an impossible plasticity—the freewheeling byproducts of synthetic realism, stuck between a logic of realism and the impossibility of its depiction. Consider cartoon electrocution: to base the visual off of the “real” occurrence would be uneventful, as an electrocuted body would simply seize up, with no visible current. The cartoon-logic version, consequently, animates bones flashing through skin in stark contrast, against a black-and-white silhouette. The x-ray vision afforded to a viewer when a character is electrocuted in a cartoon universe reinforces the limitless potential of the undying body which cartoons depict.

Gregory Kalliche’s animated video Buncha Hells takes the metaphor even further: if, for cartoons, some of the cultural cache rests in depictions of impossible phenomena or exaggerations of the familiar, what is their contemporaneous, CG equivalent? Taking its visual cues from the history of electrical visualization, Buncha Hells puts the whole gamut on display: from early and dramatic exhibits of scientific protocols to the cartoon-logic protoplasms of imagined fantasy. Tesla’s Egg of Columbus, an egg-shaped copper device used by Nikola Tesla in the 1893 World’s Fair to showcase alternating current, is reenacted— backlit by an exaggerated torrent of electrical sparks powering the egg’s revolutions. The prepackaged awe and wonder which fantastical electrical displays afford us is restaged into playful, elastic abstractions. A pickle becomes electrified as a salty conductor; a squirming electric eel fires in a switch box, and two well-placed conductive pins in a pair of severed frog legs demonstrate bioelectricity via cartoon logic. The products of this electrical-visual technoculture become forms of manipulation whose singular histories of innovation and research highlight the transductive relationship between technical culture and human proficiency.

But the exciting fantasy of technological determinism is tempered with an uneasiness in the work. Through the video’s editing, sequencing and sound design, the subject matter is pressurized and put on edge, revealing that even in its most ordered sense, electricity as a force can overcome its means of control. Buncha Hells visualizes the subconsciously-embedded arrogance in the idea that electricity is something to be manipulated and managed. It also is a testament to the fact that knowledge is not singular, but instead a veritable kismet of representations, manipulations, and perceptions. To focus our attention is to privilege a singular vantage point among the endless exchanges, pictorial conventions, and non-experiential modes one can use to understand or describe a particular subject.

Beyond the video, additional representations of electricity are actualized throughout the exhibition space. In a series of LED sculptures, energy-efficient diodes glow in amber with likeness to the incandescence of older lighting apparatuses referenced in the video. In addition to the light-emitting sculptures, the video, which is synchronized to a program controlling lighting cues, extends its own luminosity into the broader exhibition space, effectively submerging a viewer from multiple sensory positions. These intricately woven works gesture to the shared circuit of Buncha Hells as an exhibition— the works tether to each other in their condition of being plugged-in, interconnected and synchronized.

From the imperfect flow of electrons to the organizational logic in which they exist, digital media and computer-generated imagery cannot hide or transpose the mechanisms that constitute them. Here sits the genealogy of visualization, offering what storytelling offers to cartoons: a push-and-pull between fact and fiction, where realism is an admixture of both what resembles the real and an irreality which produces “realistic” effects. By combining the representational with the more-than-representational, Kalliche offers visualization as a consequence of an altered and amalgamated human vision.

Gregory Kalliche is an artist based in Brooklyn, New York. Recent exhibitions include Fall River Museum of Contemporary Art, Massachusetts; New Museum, New York, Interstate Projects, Brooklyn, and Signal, Brooklyn. Additional projects include 57 Cell, a publication that Kalliche produces featuring 3D-modeled exhibitions in simulated environments, and Pretty Days, an offsite curatorial project he co-runs with artist Harry Gould Harvey IV.

Florals by Asmite. Images by Sebastian Bach.

Gregory would like to extend a special thank you to Cari Bernard, Kyle Clairmont Jacques, Nathaniel Delarge, Taylor Hawkins, Kristin Walsh, Elizaveta Snheyderman, and Asmite.