And They Earned Eternity in a Brief Space of Time

Alix Vernet

Here Are Enshrined, Reliefs from Brooklyn Public Library, Central Branch

Glazed stoneware

132 × 110 inches

2021

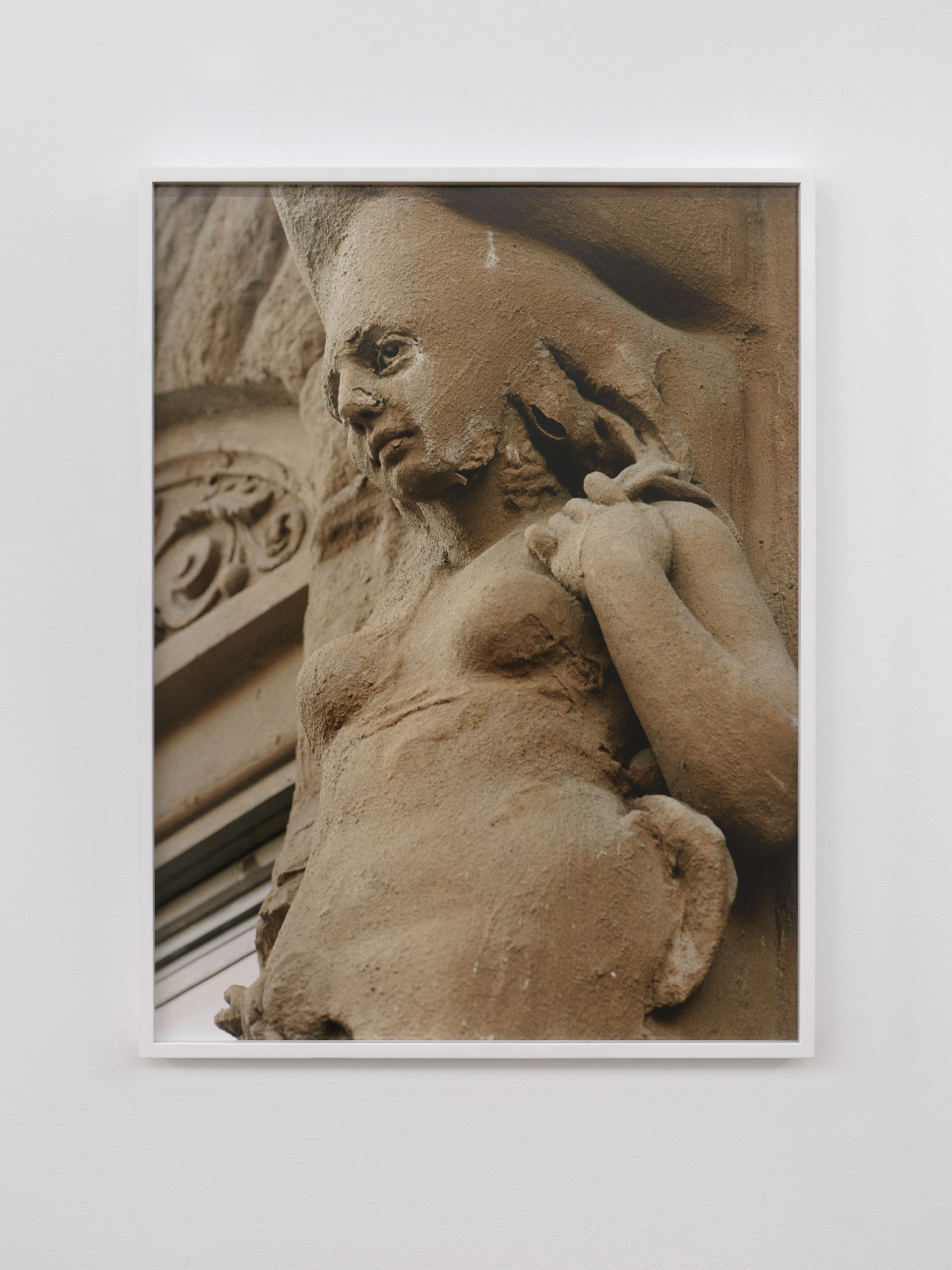

Lady, Saint Marks

Archival pigment print

25 × 35 inches

2021

Veil, 1B, East Broadway

Cheesecloth, latex, spray paint

60 × 90 inches

2019

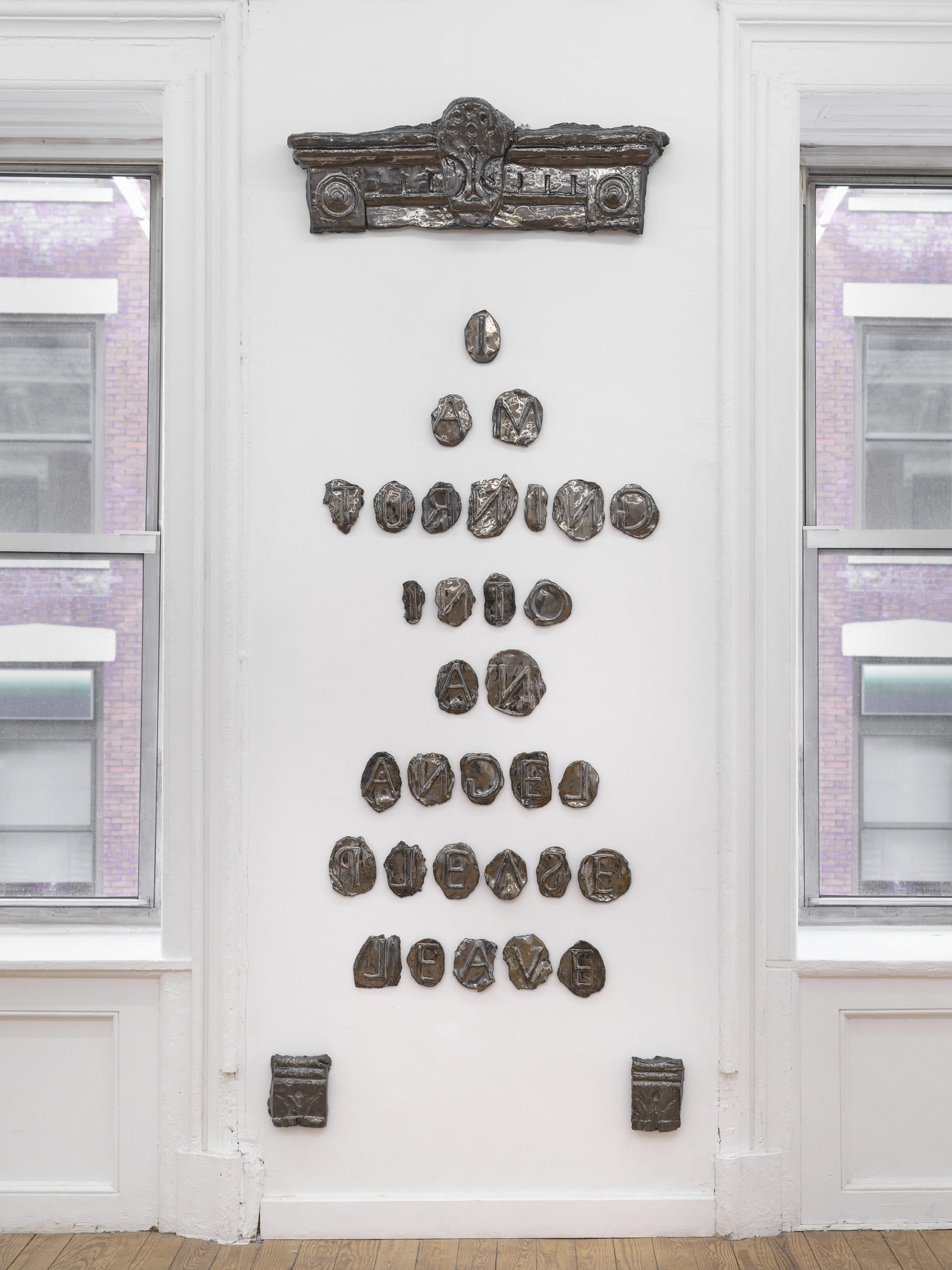

I AM TURNING INTO AN ANGEL PLEASE LEAVE, Impressions from Brooklyn Public Library

Glazed stoneware

28 × 82 inches

2021

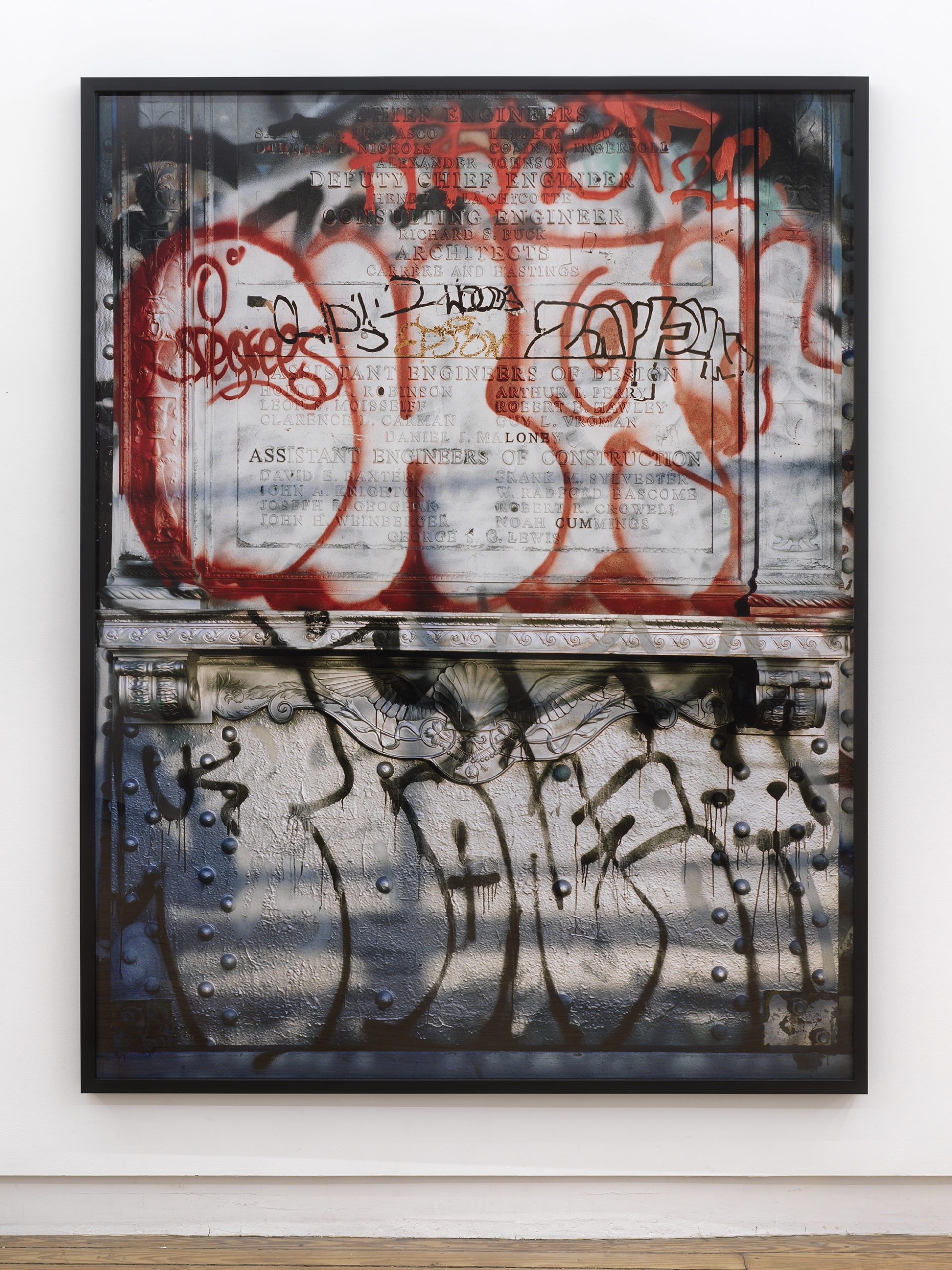

(ASS)(LONE)(CUM), Manhattan Bridge

Archival pigment print

55 × 74 inches

2018

Veil, 3A, East Broadway

Cheesecloth, latex, spray paint

58 × 91 inches

2021

Burial, Henry St

Chromogenic prints

19.75 × 29.75 inches

2023

Lady, Saint Marks, November

Cheesecloth, latex, spray paint

13 × 54 inches

2021

Hero

Glazed Stoneware

24 × 12 inches

2018

28 Jan–19 Mar 2022

And They Earned Eternity in a Brief Space of Time

Alix Vernet

Artforum, Artnet News, Document Journal

Helena Anrather is pleased to present a new body of work by Alix Vernet, her first solo exhibition at the gallery.

Alix Vernet’s work gives voice to corners of New York City often rendered mute by inattention. Artists have long set about creating typologies and records of buildings and neighborhoods facing the ever-looming threat of re-development. Vernet’s project expands on the practice of historical salvage, fusing photography, sculpture, and social practice to use buildings as raw material and highlight the capacity of surfaces to become what Giuliana Bruno describes as “the communicative interface of a public intimacy.”

Vernet has become fascinated by the complex ornamental flourishes found on many of the late 19th century buildings where the East Village meets the Lower East Side. These so-called decorated tenements are holdovers from a moment in which old traditions of handicraft collided with new systems of industrial fabrication and mass production, creating a complex and paradoxically rich visual language on buildings associated with impoverishment. These buildings appropriated design like ornate neoclassical stone and terra cotta detailing motifs that signaled upper-class status and made them a prominent feature of housing for working-class immigrants. By titling these works Veils Vernet points towards the history of shaming by 19th century housing reformers who argued that ornamentation on tenements was vulgar and veiled immoral activities and vice. Over the course of the 20th century, such ornamentation disappeared, rejected by an ascendant Modernism that, as theorists like Anne Cheng have shown, feared ornament as racialized, gendered, and other.

Vernet’s interest in these buildings inevitably drew her into the community surrounding and harbored by them. The artist went door-to-door asking to create her impressions. With the help of accommodating residents, she climbed through windows and up fire escapes to cast the delicately ornate facades. In doing so, she reveals the complex interplay between private and public, individual and collective. These works bring the viewer face to face with the communicative and expressive capacity of architectural facades, and an evocative episode in the democratizing of luxury. Held together by threadbare cheesecloth, these lightweight sculptures make architecture appear fragile, an apt reflection of buildings that are too often under threat of new development, or the everyday degradation of disinvestment.

The letter forms cast from the exterior of the Brooklyn Public Library’s Central Library at Grand Army Plaza are the largest example of the street casting practice that Vernet has previously deployed when appropriating texts from other public monuments in New York City. Like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans—both of whom frequently photographed billboards and other street signage as vernacular American poetry—Vernet identifies the language of public inscriptions as a baroque institutional voice, one that is ripe for playful re-signification. Language becomes a readymade and a found material. Atomized into individual letters and re-written into new texts, the highly formal language of public address written into the Central Library is deconstructed and reconstituted as something shiny, new, amorphous and flexible. A photograph of a metal plaque on the Manhattan Bridge shows one more surface that acts as an interface for public intimacy. Covered in successive layers of graffiti, the plaque has become a palimpsest of individual gestures, and the multivocal nature of life in cities, a series of ephemeral entries in the thick texture of the city’s surfaces. By reimagining the solidity and permanence of architecture as moveable and ultimately ephemeral, Vernet reveals the surface as the site of contact between an individual and their environment.

— Brandon Eng