The Apple Stretching

Yuji Agematsu, Kamrooz Aram, Seth Becker, Greg Carideo, Paloma Izquierdo, Y. Malik Jalal, David L. Johnson, Vijay Masharani, Erin Morris, Nicky Nodjoumi, Carlos Reyes, Count Slima, Tabboo!, Alix Vernet, Kristin Walsh

DPW, Church St.

Glazed stoneware

2023

Sweet 'N' Low

Oil on linen

2023

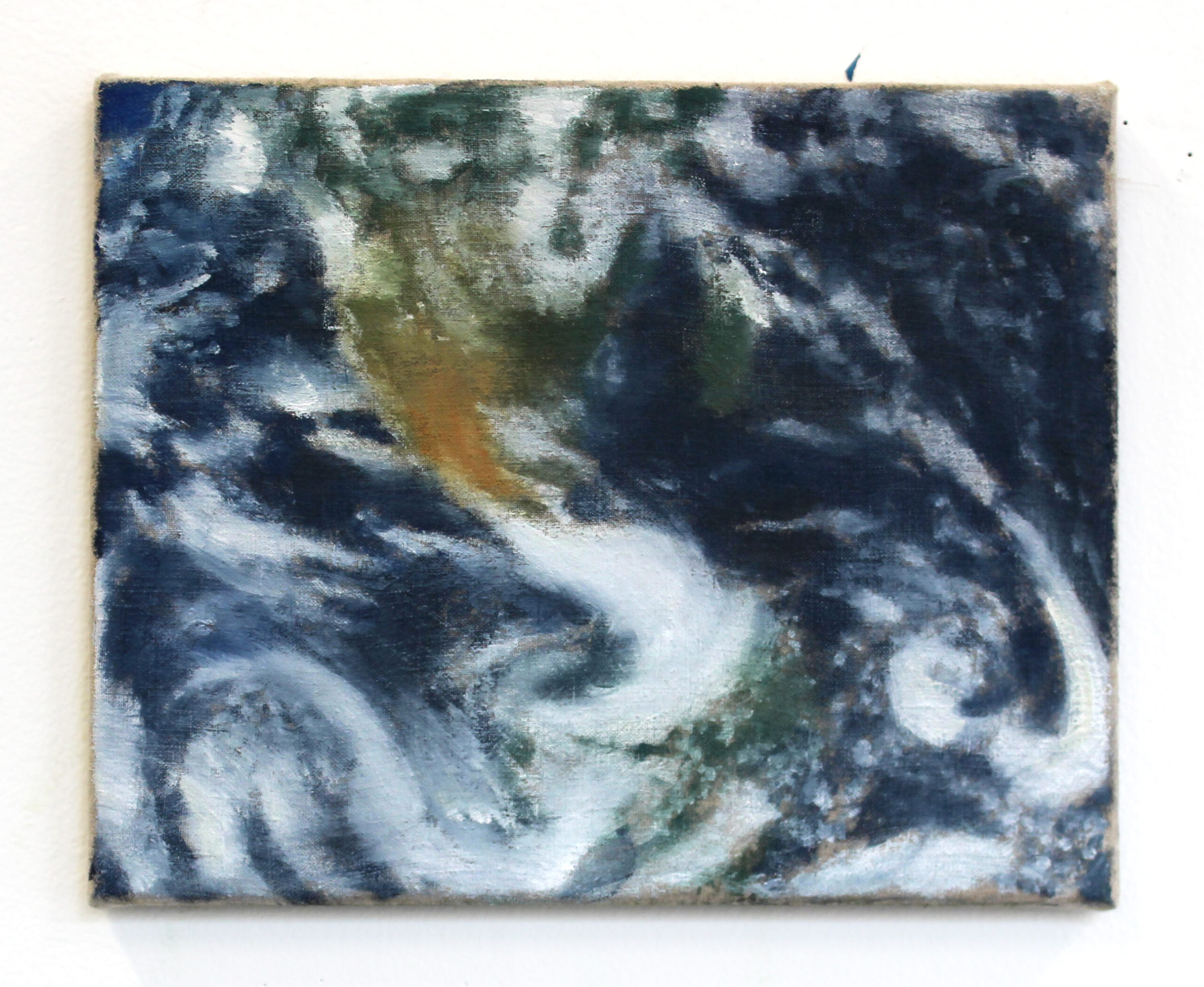

After NASA's Blue Marble

Oil on linen

2023

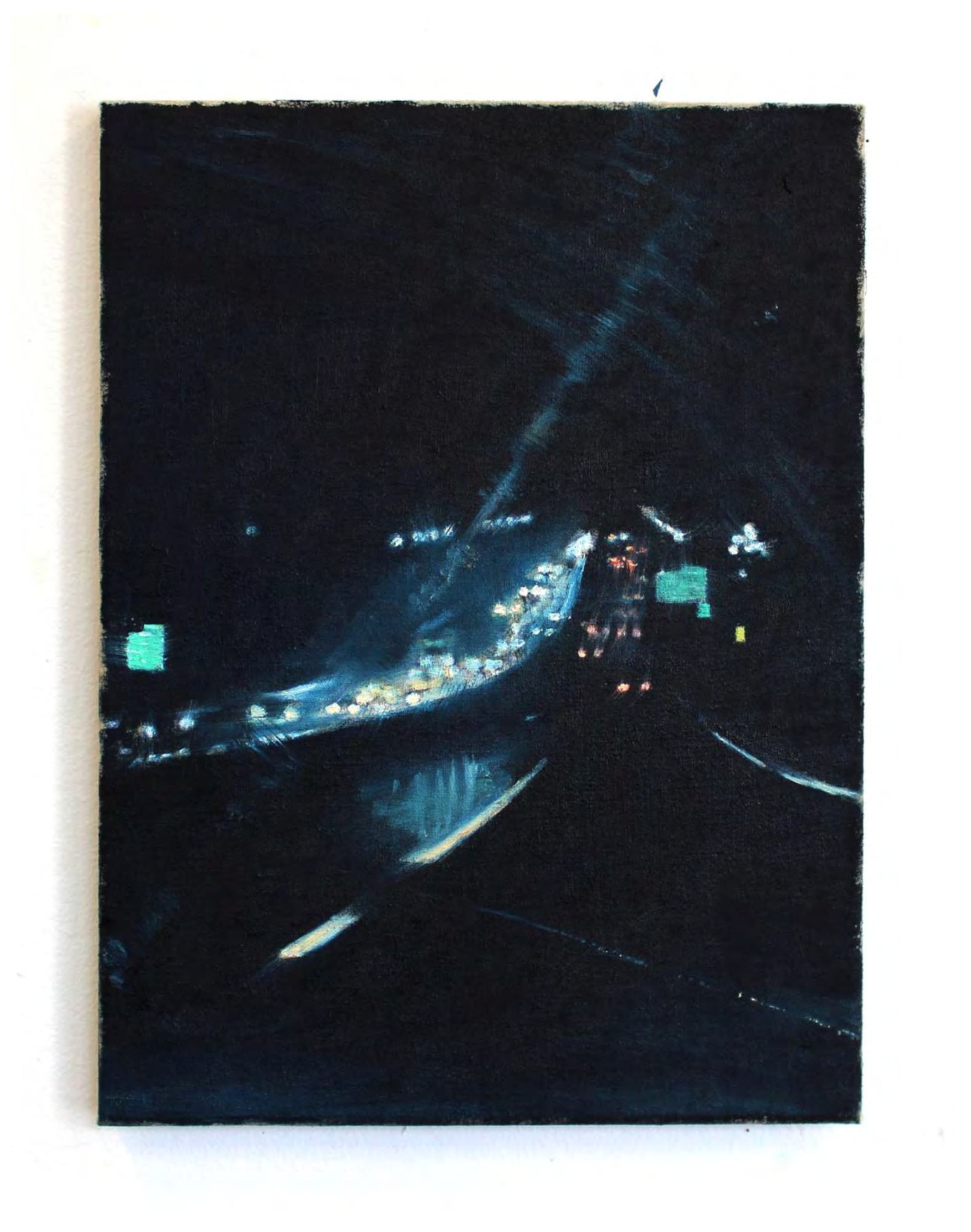

I95

Oil on linen

2023

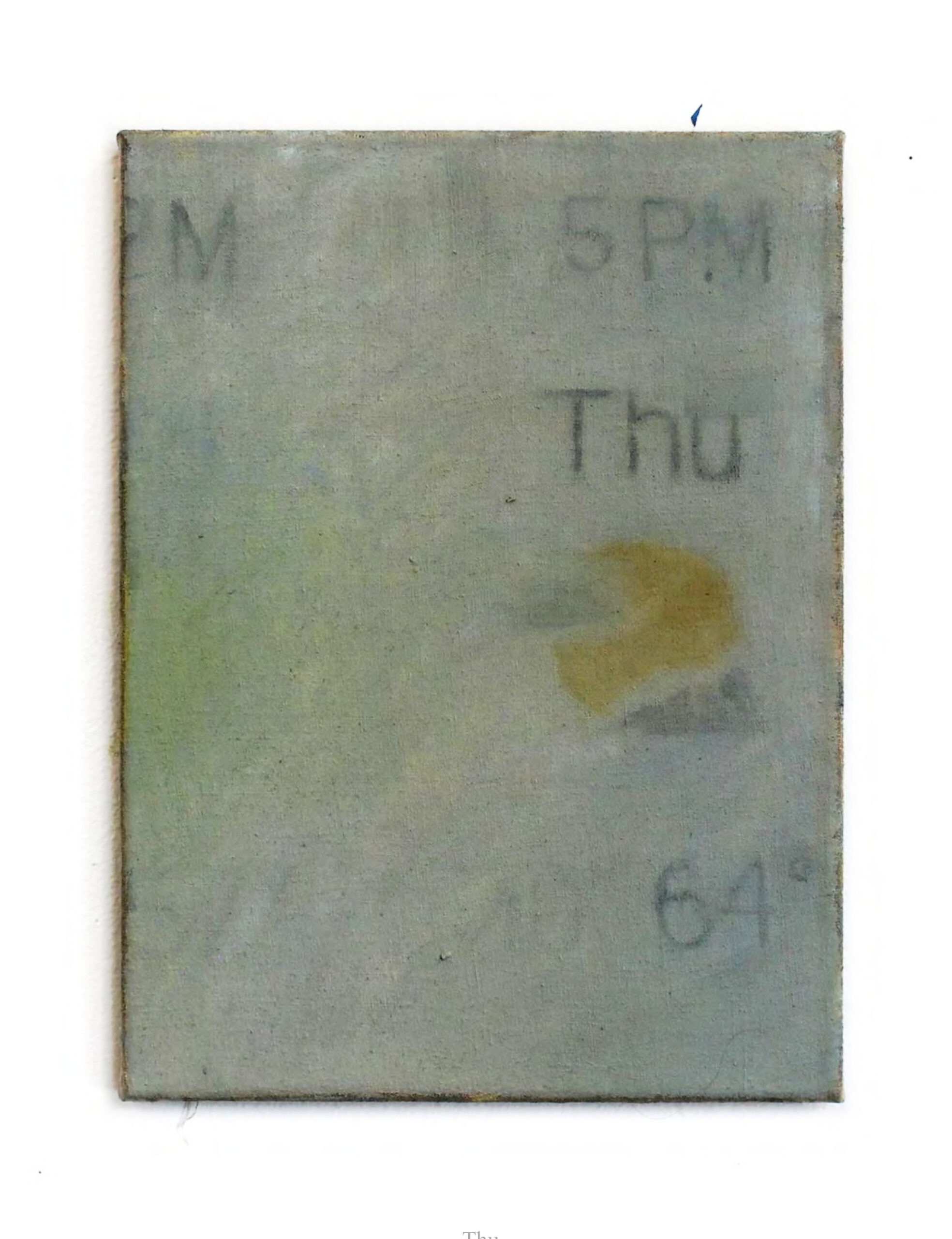

Thu

Oil on linen

2023

ABM

T-shirt shoulders, found striped shirt, found shoe heel, steel, paint, and rust

2023

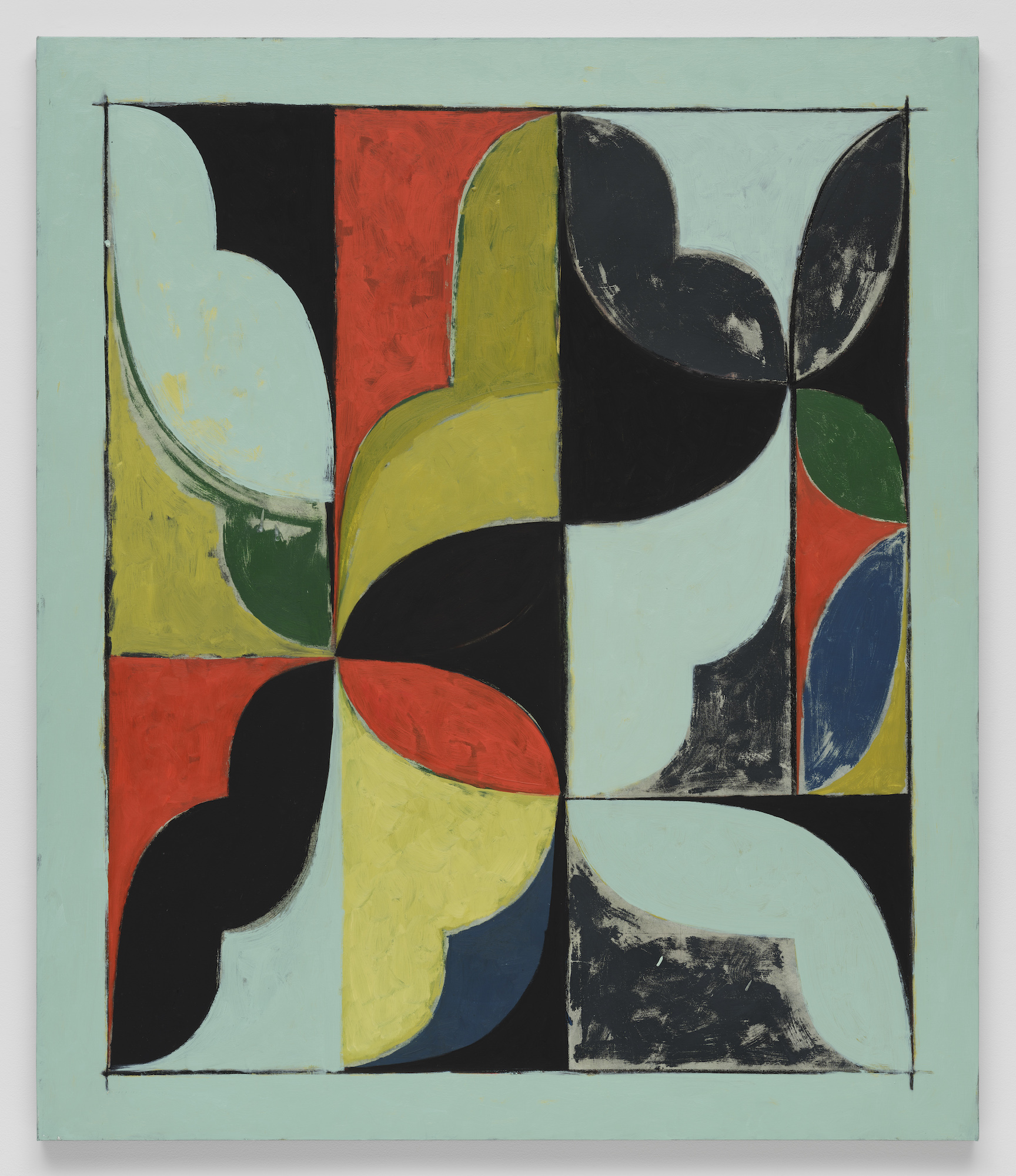

Arabesque Composition for a Modern City

Oil, oil crayon, and pencil on linen

2023

Engine no. 6

Aluminum, stainless steel, cotton wick, and paraffin oil

2023

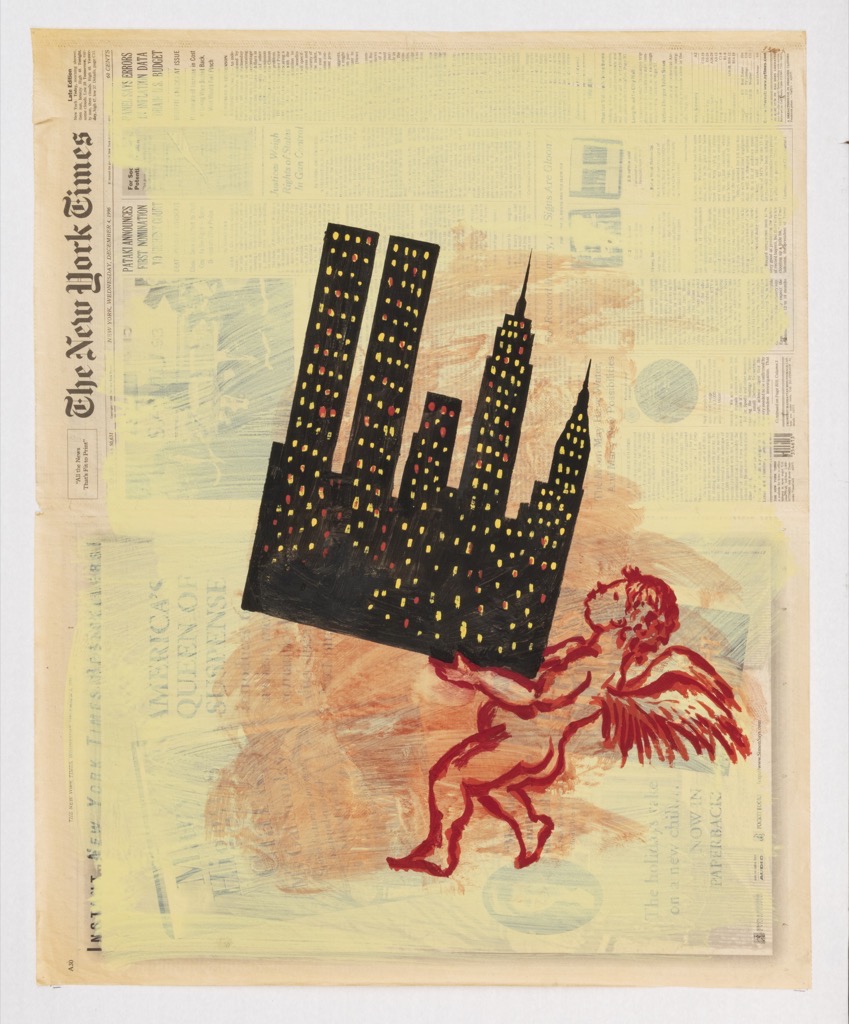

New York Times, Wednesday, December 4, 1996

Mixed media on newsprint

1996

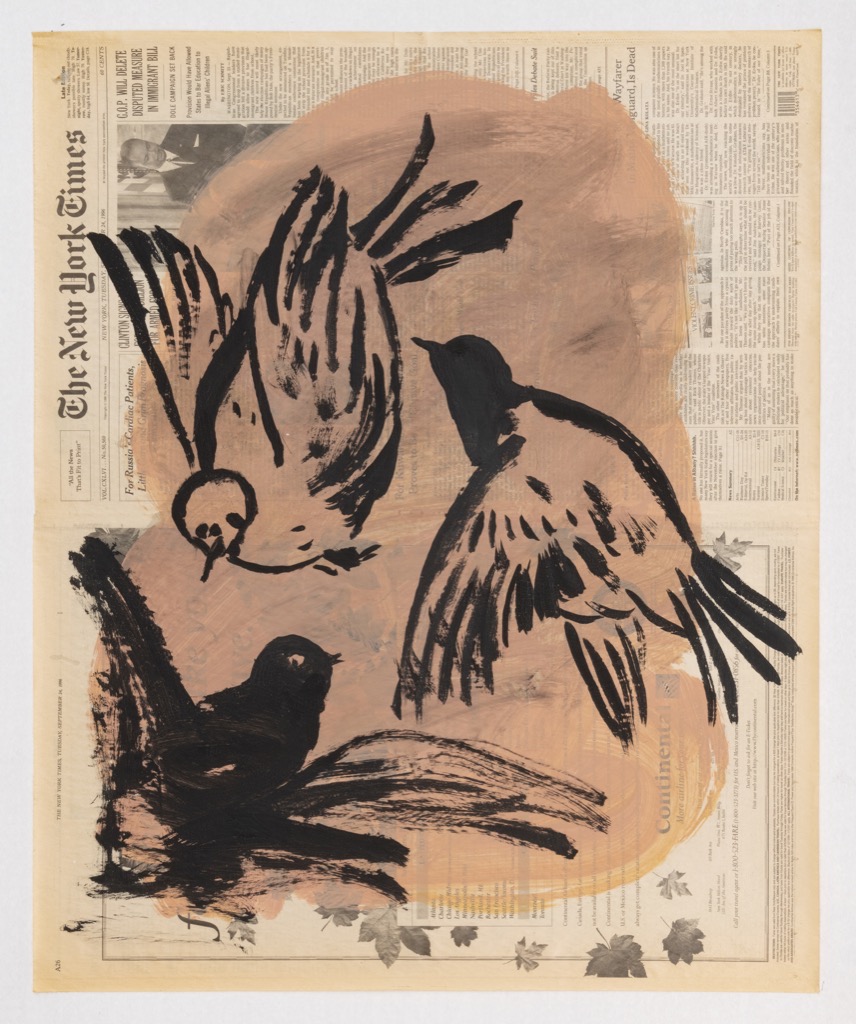

New York Times, Tuesday, September 24, 1996

Mixed media on newsprint

1996

Money Rail (left)

Glass, brass, bills, coins

2023

Sunset Out My Window

Acrylic and glitter on canvas

2023

Winter Moon Over Manhattan

Acrylic and glitter on canvas

2023

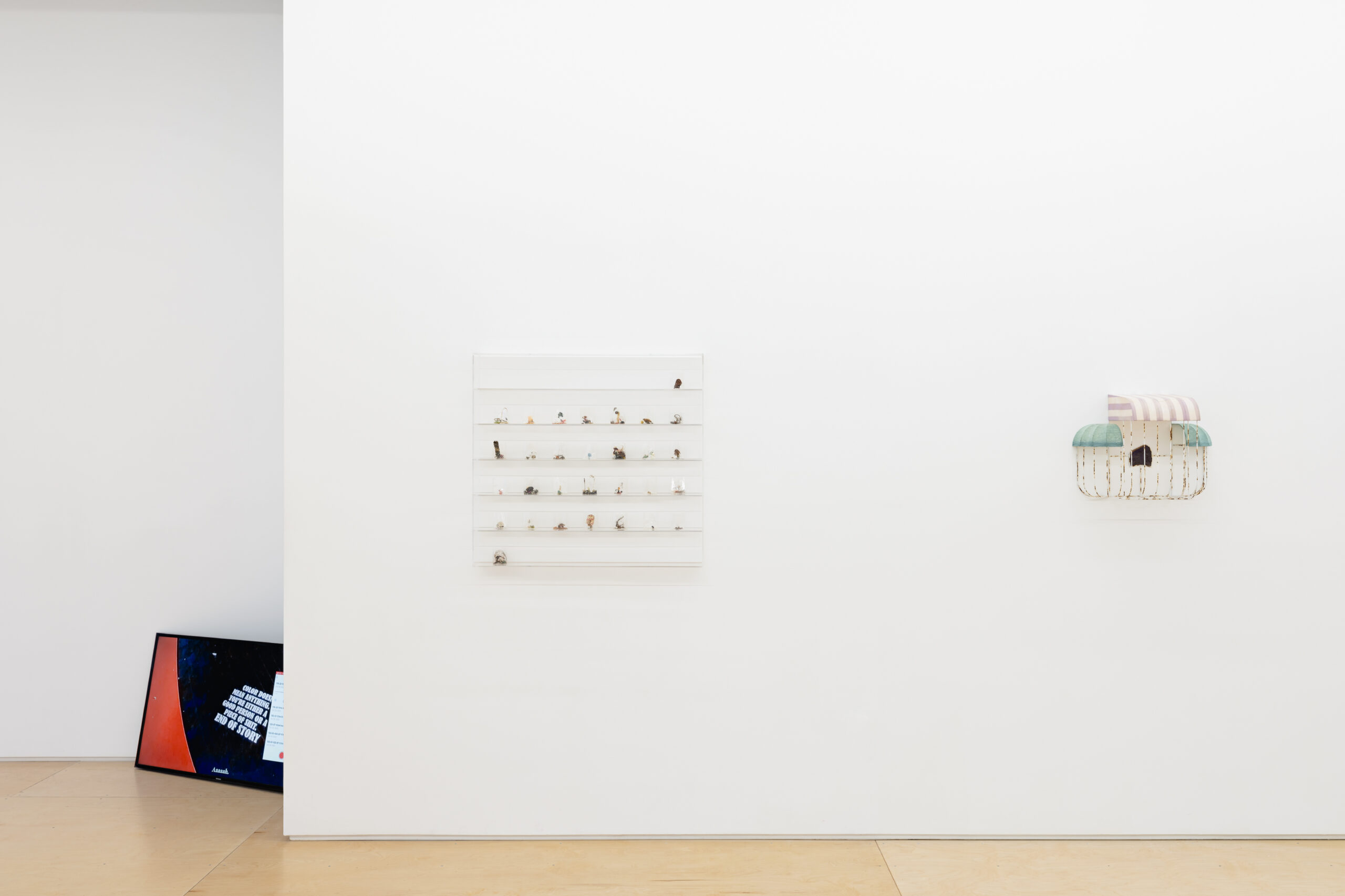

zip: 06.01.13 . . . 06.30.13

Mixed media in cigarette cellophane wrappers (30 units) on wood backed acrylic shelf, latex paint

2013

5 Jan–10 Feb 2024

The Apple Stretching

Yuji Agematsu, Kamrooz Aram, Seth Becker, Greg Carideo, Paloma Izquierdo, Y. Malik Jalal, David L. Johnson, Vijay Masharani, Erin Morris, Nicky Nodjoumi, Carlos Reyes, Count Slima, Tabboo!, Alix Vernet, Kristin Walsh

Helena Anrather is pleased to present The Apple Stretching, a group show following threads of care, civic life, detritus, seriality, and surprise. In the words of Grace Jones, ‘No, it ain’t some kind of ill wind, no, it ain’t the world coming to an end, Just the apple stretching and yawning, just morning, New York putting its feet on the floor.’

Since the early 1980s, Yuji Agematsu has been collecting discarded debris during his daily walks around New York City. The sculptural assemblages that he creates with the collected trash become a record of specific days, months, or decades, tracking the transmutation of the city.

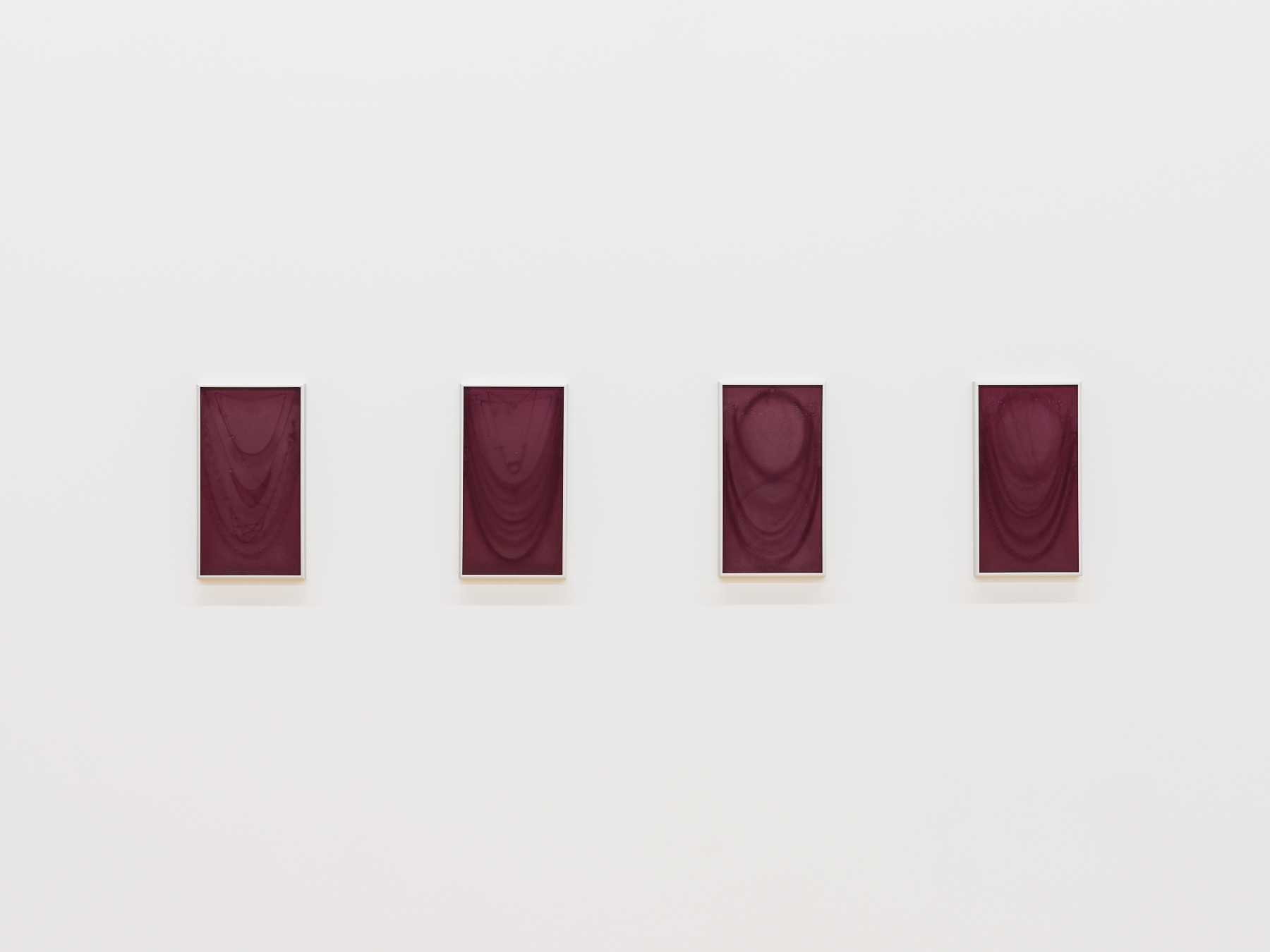

Kamrooz Aram’s paintings recombine modernism and ornamentation. Approaching the canvas as a wall, a kind of palimpsest that registers traces of his additive and subtractive processes, his work is redolent of city surfaces.

Seth Becker’s paintings deal with the familiar and the strange in equal measure, often obscuring which is which. Many of Becker’s scenes take place in a gloomy haze that evokes the experience of memory. In this instance, Becker paints the entrance of the Children’s Zoo in Central Park.

Greg Carideo’s wall-mounted sculptures draw from the built environment of the city. Often resembling commercial awnings, they are born out of his fascination in the ways that care and wear are expressed materially. Each sculpture houses a single shoe sole from his collection of discarded soles he has found in the street, speaking to the bodily aspect of form and function.

Paloma Izquierdo examines social spaces and rethinks how social architecture is perceived and used. Her chain-link fence made of glass subverts its original purpose; her hollow glass handrails are now invitations to make a wish by leaving a token behind, like coins tossed in a fountain.

Y. Malik Jalal employs the frame as a device to contain, contextualize, and question authorship, care, and legacy. Jalal sifts through family photographs and memorabilia on eBay, combining these found images with welded iron and car parts. Jalal’s collaged works join the pictorial and the sculptural.

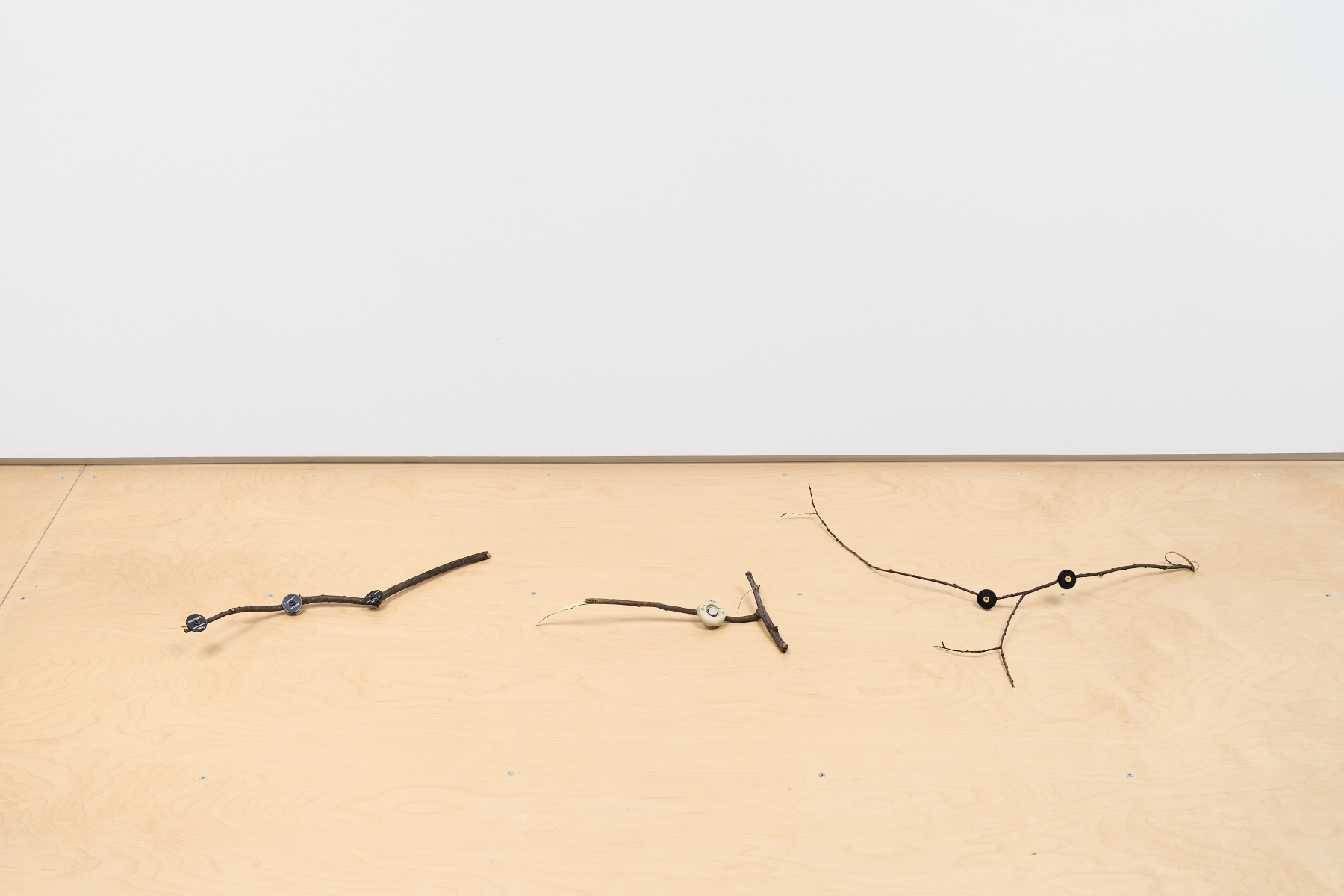

David L. Johnson investigates the different processes of change that happen in the city—his work observes, documents, and sometimes intervenes with these processes. Johnson’s recent token sculptures disrupt patterns of private surveillance that have recently been implemented around the city in the form of scannable data disks illegally embedded in trees.

Vijay Masharani’s manipulated video work addresses the gamification of existence and the potential inherent in the city. Give me that fucking content, Universe was filmed around his studio in Queens and ponders where answers are held, and who holds them.

Erin Morris’s paintings explore scale and its relationship to time and image. Encompassing the entire planet or the corner of a sugar packet, the paintings form constellations of time and place at once universal and specific.

In 1996, finding himself short of money for materials, Nicky Nodjoumi began painting on the front page of The New York Times after reading it each day, developing a daily diaristic practice that was equal parts a forum for aesthetic experimentation, an exploration of his inner life, and a meditation on world-historical events in real time. As a political exile without a passport, Nodjoumi was unable to travel and relied on the Times for creative inspiration and a window onto the world.

Carlos Reyes’ practice recontextualizes sites of longing and joy, including his ongoing project of collecting Canal Street’s sun-bleached jewelry displays, which he then reconfigures into arrangements that encourage pause and reflection.

Count Slima is a downtown debonaire and local poet active since the 1970s. He has made daily meditative poems ruminating on the seasons and shifts in the city for decades, dedicating five or six hours every day to meticulous stenciling and personal reflection.

For the last 40 years, Tabboo! has been painting New York City, his greatest muse. Working primarily from his Alphabet City apartment, his depictions of the cityscape are intuitive and dynamic.

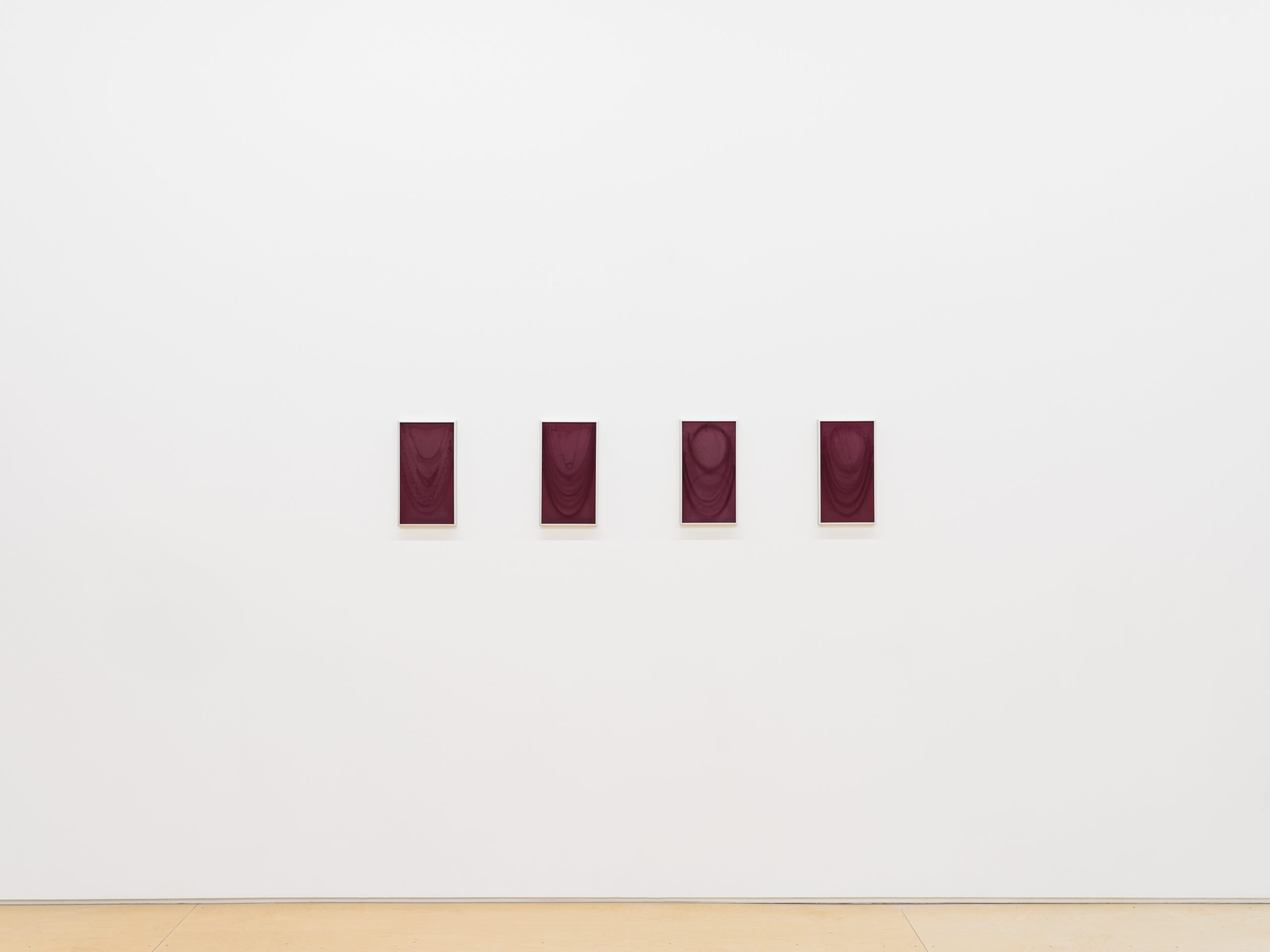

Alix Vernet’s practice raises questions about access and the border between public and private. Her process is also a lesson in looking closely: finding beauty among competing city architectures. Vernet’s works are cast from local buildings, monuments, and other public objects. By rearranging these fragments, Vernet brings attention to the fact that the physical makeup of a city is in constant flux.

Kristin Walsh’s welded aluminum sculptures reference the seen and unseen infrastructures that undergird the city. They are quiet animations of the passage of time; in this case a candle illuminates what resembles a discarded machine part. While this object is immediately visible as detritus, it is less visible as currency—aluminum’s recyclable property makes it valuable. The regulation and circulation of the material by the city is just one of many systems that Walsh is interested in revealing.