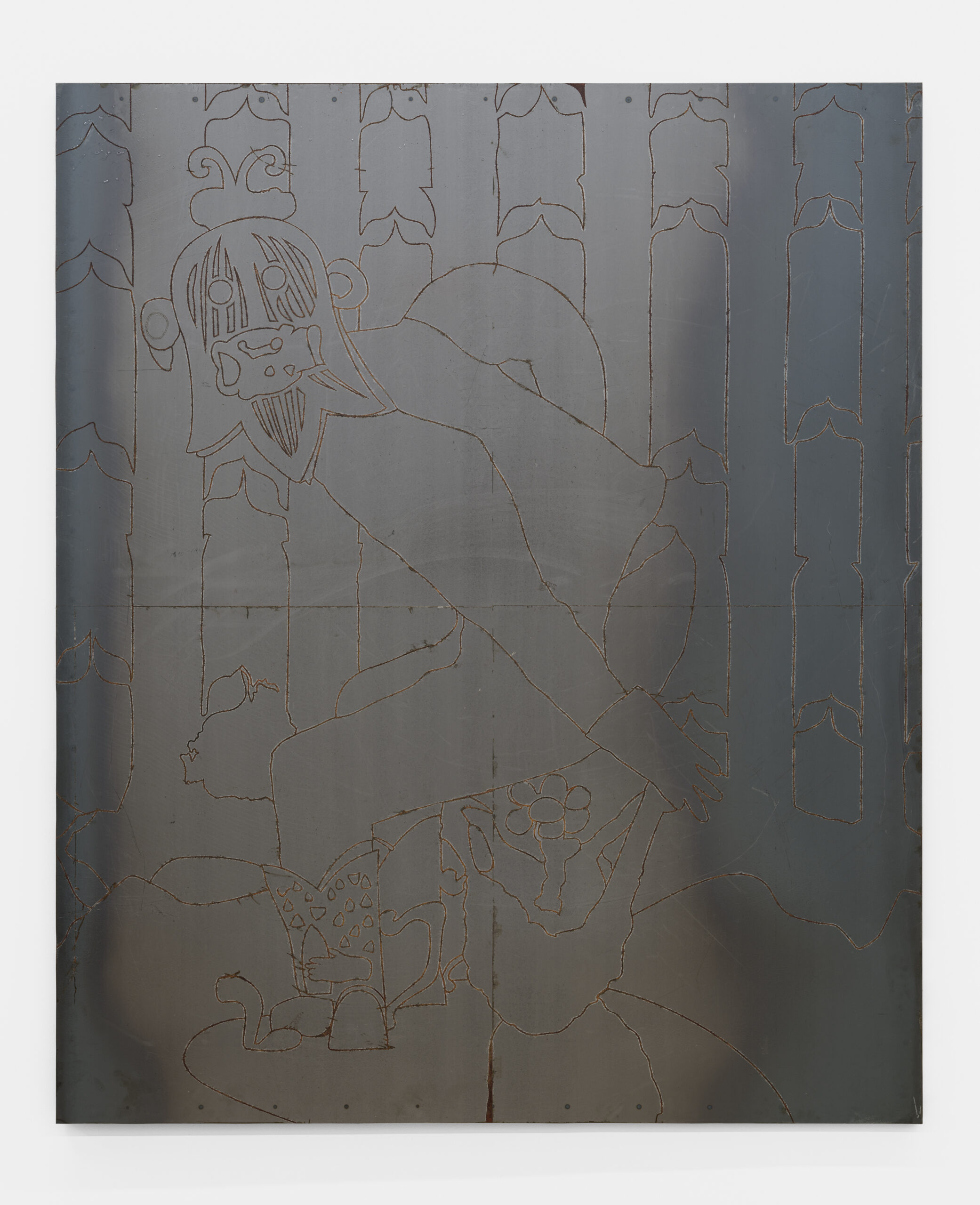

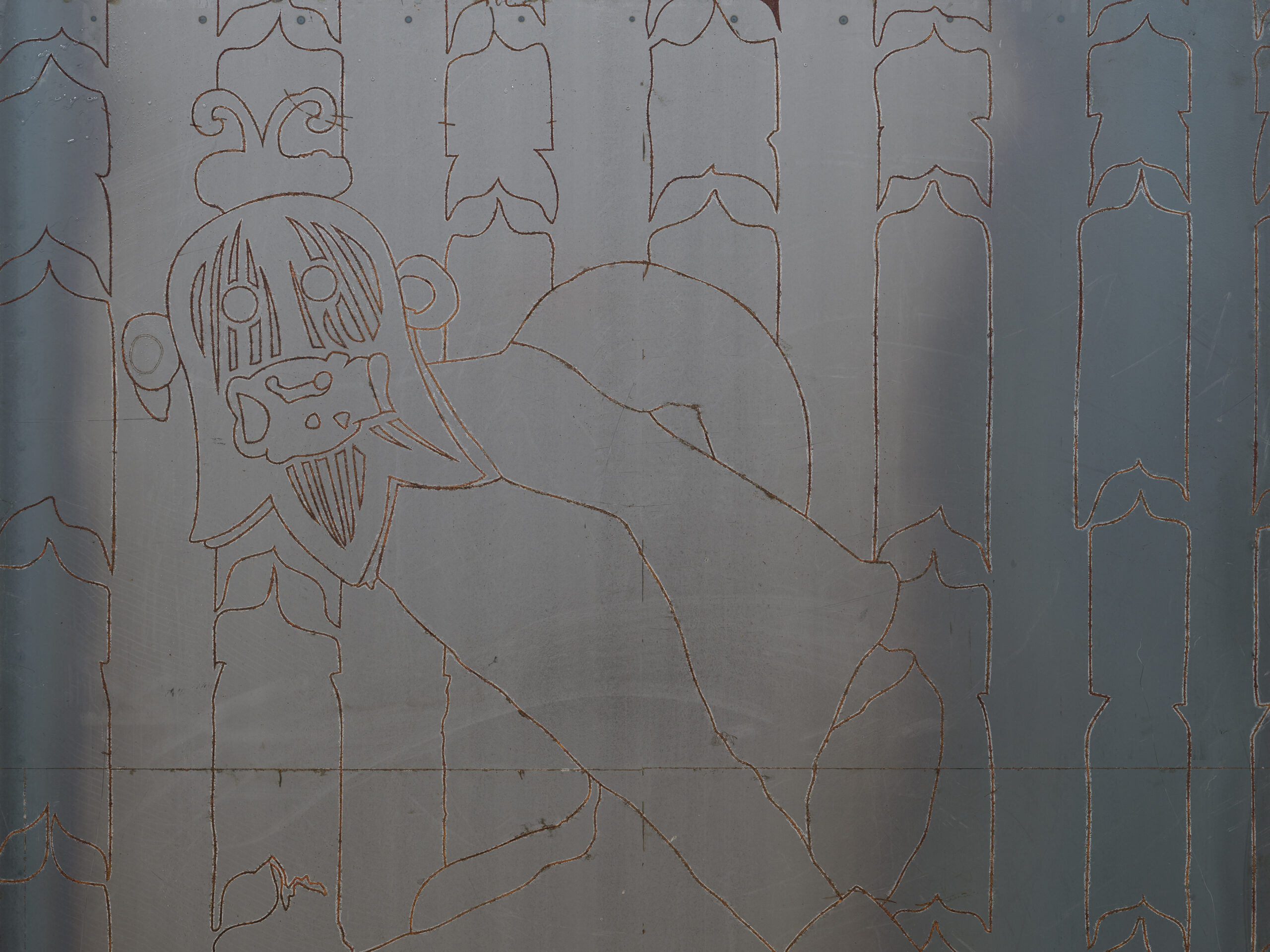

Dampen the flame; Extinguish the fire

A dog without a master (Rust)

Steel and iron oxide

59.5 × 72 inches

2022

8 Sep–22 Oct 2022

Dampen the flame; Extinguish the fire

Azza El Siddique

Monuments to Grief

The sumptuous fragrance of bukhur, the Sudanese incense, wafts through the air. It emanates from burning water lilies, resting on a low basin flanked by two tall structures that resemble a pair of stelae guarding an altar. Water trickles down these two skeletal constructions, slowly eroding unfired-clay vases placed on wire shelves. Positioned at the end of the oblong room, this crypt-like configuration is the arrival point from a larger space demarcated by more gridded metallic structures, empty and varying in height. Strewn across this enclosure are myriad objects: drawings etched in steel, a baseball cap, a sculpture of a two-headed snake on a plinth. The ambience is somber, evoking a mausoleum.

Rich with metaphor, Azza El Siddique’s exhibition forms a constellation of objects and site-specific interventions that appear to cast a spell. The references are both strikingly erudite and inscrutably personal.

Some of the iconography speaks to El Siddique’s research into the myths and creeds of ancient Egypt, particularly the Nubian dynasties. She contemplates how the state conditioned society through religious practices to which magic was integral, orchestrating an intimate relationship between the living and the dead. Her work is redolent with those subtle, elusive, and layered primordial semiotics, pointing to the slippery meanings that have always governed our lives, despite our denials. We are surrounded with polarities that are ostensibly contradictory, but which tend to bracket our existence: past and present; real and imaginary; visceral and rational; frailty and strength; spiritual and profane; self and other; alienation and belonging; and, of course, life and death.

The contemporary symbols, inspired by El Siddique’s private recollections and her community’s folklore, are more difficult to decipher—and therein lies their lure. The aroma of incense might conjure warm domestic memories, or Muslim mortuary rituals, or perhaps even healing, when its smoke anoints those seeking protection. For some, it might simply signify an “other” culture. El Siddique recognizes in the fleeting smell of bukhur the strength of Sudanese women, and in its ashes the decay of death.

While she builds on previous permutations, and even though she often revisits the tomb of Taharqa—the Black pharaoh who erected the largest of the Nubian pyramids in northern Sudan— El Siddique’s skeletal structures do not solely suggest funerary ruins or maps of an underworld. The gridded frames flirt with the power of architecture, from its potential to shelter and enable gathering, to its manipulation toward more sinister and oppressive ends, such as social engineering or incarceration. But hers is a different kind of architecture, one in which the ravages of time might be felt. She charms us into momentarily inhabiting her constructed world, where materials might age, disintegrate, and vanish. The concept of entropy has been one of her primary preoccupations. She distills ideas and translates them into spatial assemblies, which she then dismantles and destroys.

It is no coincidence that El Siddique, of Northeast African descent, has taken a dive into Nubian history. But this is not just a way of reconnecting with her cultural heritage, or of finding solace by probing the question of mortality, opening a window onto the mystical realm of the dead. And although her work is especially pertinent today, as we bemoan countless lives claimed by a global pandemic—over a million in the US alone—it is also more than that. For her, those ancient civilizations offer a mirror image of the modern world, and the parallels are especially evident in the cruelty inherent to the surreptitious workings of power, the wrath of which is usually endured by the underprivileged or by those perceived as minorities who might undermine dominant ideologies.

But we are drawn into El Siddique’s installations not merely intellectually, and we do not dwell in them simply viscerally, but somatically too. She choreographs our experience around structures, objects, and sensations that heighten our awareness of the relationship between our bodies and her interventions, and between those and the larger spatial envelope. This might be reminiscent of Minimalism, or even some Land Art, but El Siddique eschews the sterile emphasis on form and scale alone. Her work is textural, at times even ornamental, sensual, craft-inspired, and continually morphing into other states, as she experiments with new materials and techniques.

The work is also a type of sublimation—not as a defense mechanism but as a way of converting ineffable sentiments into physical and sensorial form. This is why there is something uncanny when we stand within one of her exhibitions: we are not passive but unwittingly partaking in a communion, attending a vigil.

It is easy to be captivated by one or more elements in El Siddique’s exhibitions and to lose sight of what, I believe, underlies much of her work. Unifying her delicate yet precise gestures, evocative spaces, and enigmatic allegories—many of which are memento mori of sorts—is a deep melancholia. There is an overwhelming sense of sadness, soul-nourishing for those of us who have experienced loss, and resonant with a humanity that mourns its precarious collective existence in a world in which the possibility of an impending environmental, economic, and cultural collapse is all too real. The work is an elaborate elegy, and sorrow permeates the space as intensely as the smell of incense.

El Siddique’s work also cannot be understood without accounting for the haunting specter of displacement, of the experience of being plucked from one’s ancestral homeland, unable to ever reconcile ourselves with what that violent rift might mean, especially in settings that relentlessly remind us of our difference—rendering us incapable of identifying with this or that home, neither here nor there. With its sepulchral undertones, her work laments a once-nourishing culture withering in exile and honors precious ones lost, departed always too soon, leaving us ever more estranged. Her exhibitions, in their fragmentary, anecdotal, and open-ended form, are nomadic commemorations that she packs and unpacks, to be deployed wherever she goes. They are monuments to memory, to grief, and to a longing, unfulfillable and unextinguishable.

—Amin Alsaden

Photos by Sebastian Bach.