The Manner of Working Events

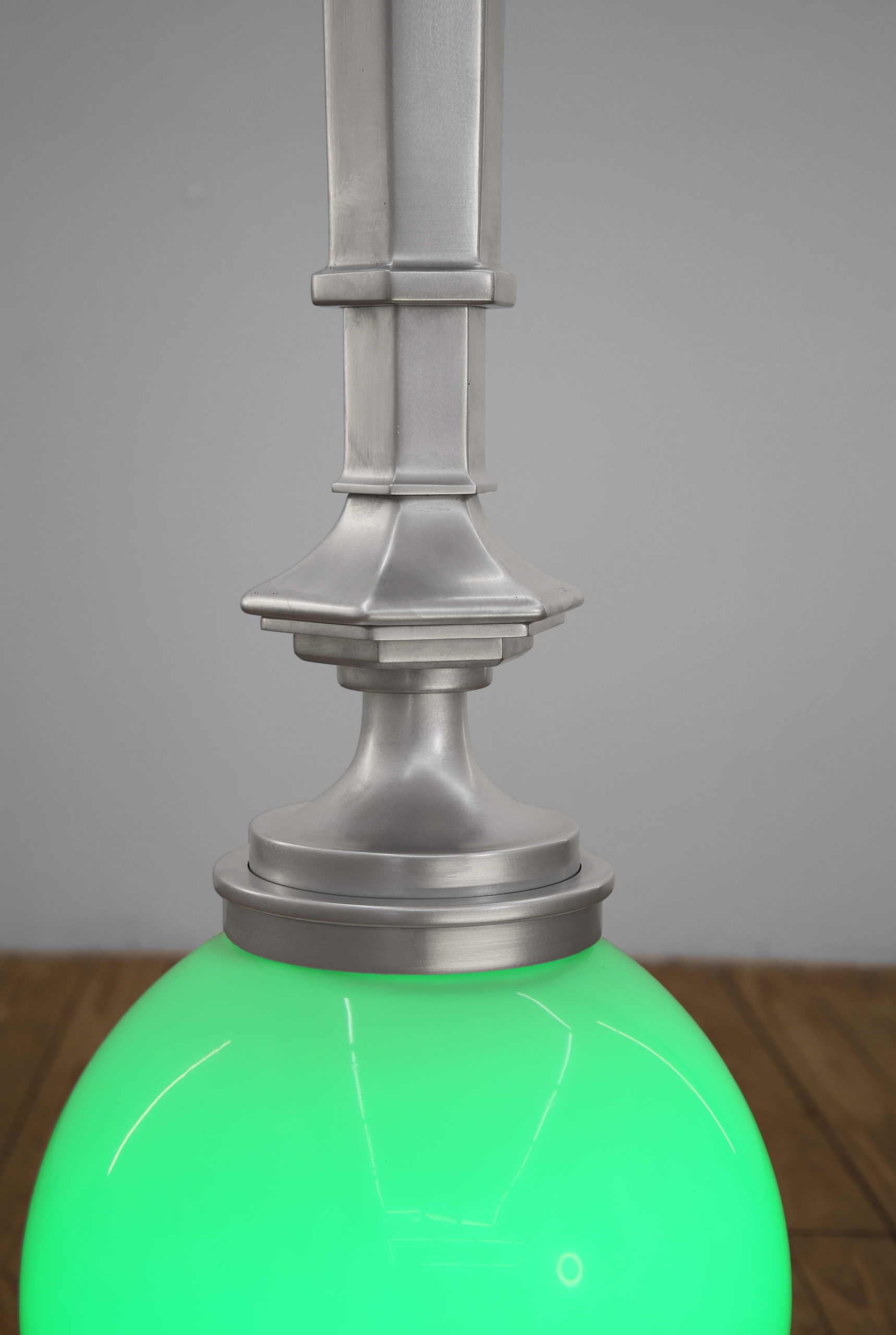

Indicator 1

Aluminum, glass, and steel

2021

Gonna Get Along Without You Now (Tanker car)

Color video with sound, Sony PVM monitor, media player

3:31 minutes

2020

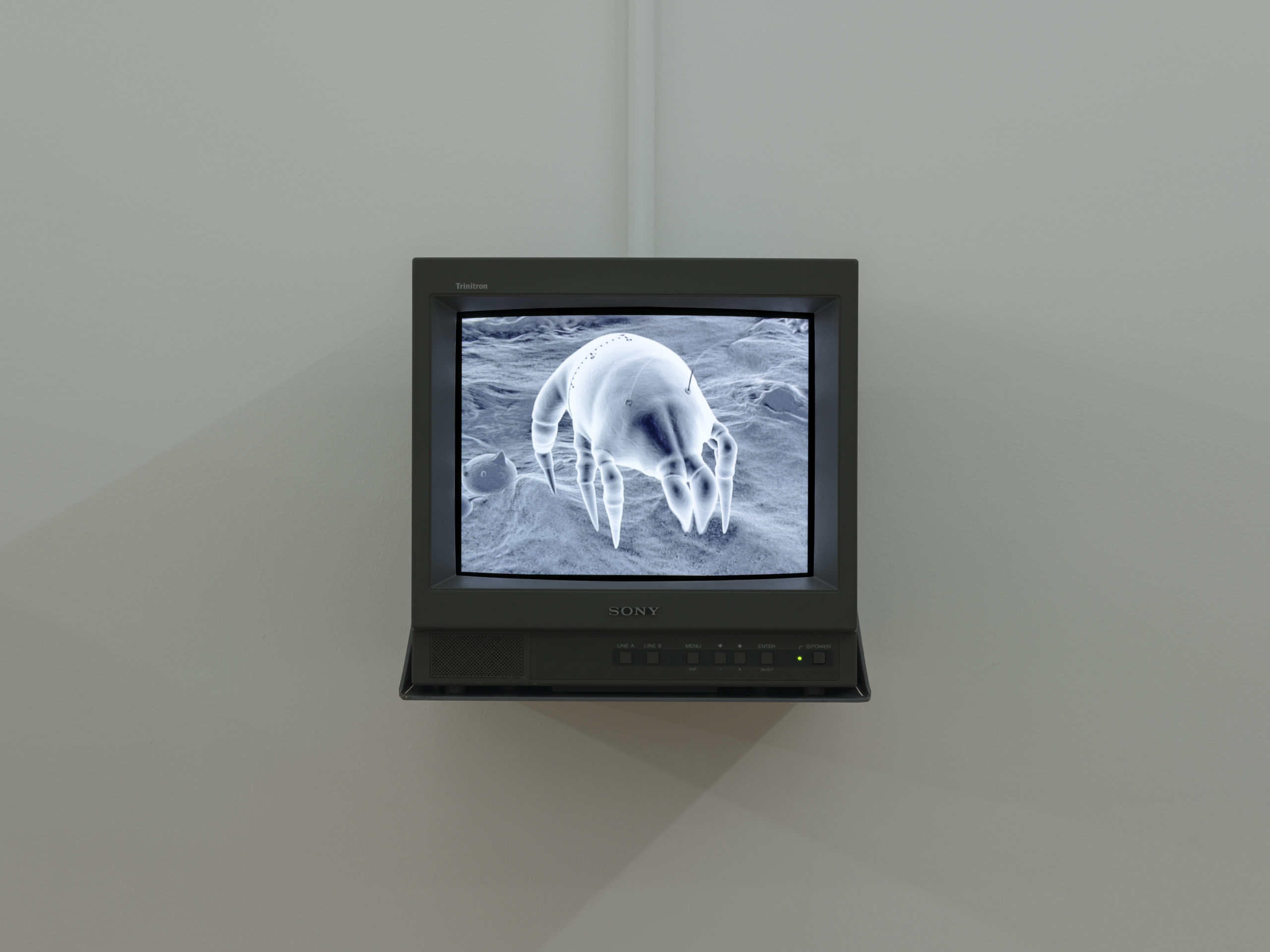

Gonna Get Along Without You Now (Dustmite)

Color video with sound, Sony PVM monitor, media player

3:31 minutes

2020

Gonna Get Along Without You Now (Burning Log)

Color video with sound, Sony PVM monitor, media player

3:31 minutes

2021

Indicator 2

Aluminum and LED lights

2021

Carrying Daylight

Color video with sound, Sony PVM monitor, media player

2:15 minutes

2021

Melodic audio segments by Mikey Enwright

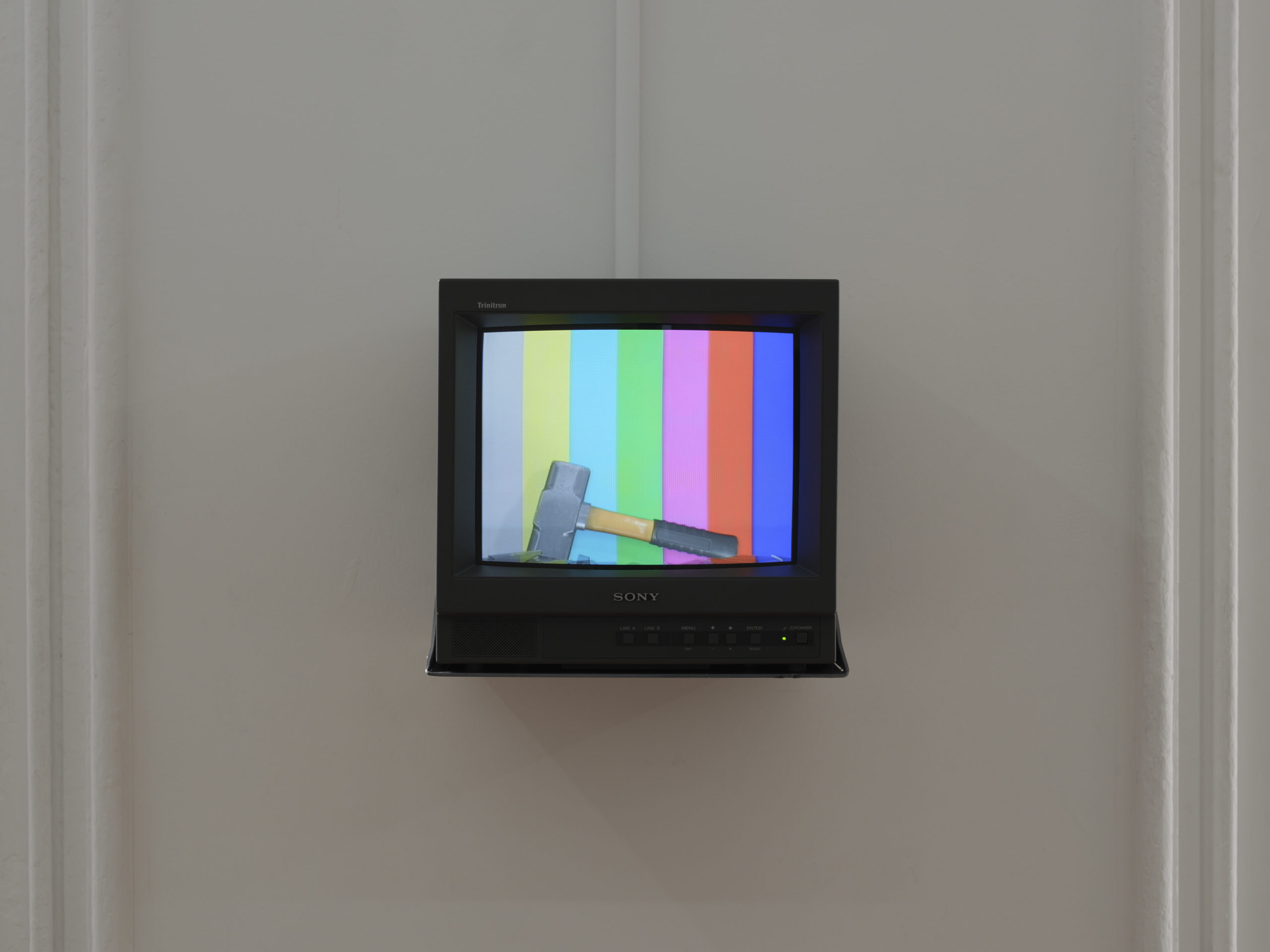

gckcolorbarswithmallet.2021

Color video with sound, Sony PVM monitor, media player

2:06 minutes

2021

12V Hermitage

Color video with sound, Sony PVM monitor, media player

2:00 minutes

2020

20 Mar–15 May 2021

The Manner of Working Events

Kristin Walsh and Gregory Kalliche

Although he’s hardly a household name, the 19th century illustrator James Tilly Matthews holds a position of modest infamy not in the history of art, but medicine, as the first person diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. His technical drawings, completed during his time at Bethlem Royal Hospital in London, centered around the “Air Loom,” an insidious mind-control machine that he believed to be brainwashing public figures; Matthews thought the machine to be implicated in nearly every political crisis of the era, from the French Revolution onward. Of course, the content of his conspiratorial vision is inseparable from the context in which it developed, namely the carceral institution of Bethlem itself, where patients were restrained, isolated, and abused. For Foucault, the clinic signalled a definitional transformation in what it meant to be mad, that relegated the mentally-afflicted to a status of near total alterity. Spectatorship was part of this redefinition, as the hospital opened its doors to the broader British public to gawk at its patients as late as 1815. So, fantastical as Matthews’ vision was, its essence seems attuned to something that was actually happening: through the diagnostic operations of the clinic, certain subjectivities were designated as non-normative and therefore deserving of treatment in the form of, in many cases, mental and physical harm. This arrangement lacks the exceptional zeal of “brainwashing,” and seems more banal, and insidious.

Both Kristin Walsh and Gregory Kalliche probe the influence of machines on human thought, exploring how networks of interconnected machinery are woven into the fabric of daily life. For instance, in Walsh’s Indicator 1 (2021), a protruding subway lamp is part of a broader infrastructural organism that includes not just the entire network of tunnels, trains, and everyone who maintains them, but also the forms of organized social life that develop through—and depend on—the subway. Since she constructs each of her pieces from raw materials, Walsh’s practice is also contoured by the dynamics of the aluminum market, which are influenced by geo-political jockeying among world powers, and distributional strategies like “just in time” logistics, which aim to keep goods in perpetual motion. The complex animacy of these global systems seems to register in the anxious ticking of the work itself. Yet the relationship between part and whole is destabilized by the lamp’s immaculate quality. The sculpture is pristine and gleaming—a blemishless, metonymic prop. It seems conspicuously unreal, unrelated, as though it were imported from another timeline. This tension, in which an object seems to simultaneously hail and disavow its structural context, is ominous, and suggests that we are situated within a predatory system that habitually covers its tracks.

Kalliche’s 3D animations combine the narrative looseness of experimental cinema with the slick, weightless rhythm of commercial advertising. Like Walsh’s fabrications, the objects he animates often double as illustrations or diagrams of larger systems. In his tripartite Gonna Get Along Without You Now (2021), three disparate forms have been retooled into five-minute egg timers, yielding a cryptic work in which a single timescale is the common factor for three non-human actors: a domestic house pest, a tanker car, and a log smoldering in the afterlife of a campfire. When the timer runs out, the taunting vocals of Skeeter Davis’s 1962 pop classic (from which the work borrows its title) fade in, implying that the countdown was to the ultimate form of planned obsolescence: extinction. But no such uniform eschatological threshold exists, as the apocalypse is not a singular momentous event, but an ongoing, protracted phenomenon, asymmetrically distributed according to race, class, citizenship, and mobility. So, Davis’ needling sing-song voice seems to imply a spectral presence of insincerity, or an ulterior motive, that deploys a disingenuous image of a universal humanism conjured in the shadow of oblivion. Perhaps no work in The Manner of Working Events better epitomizes this situation than Kalliche’s gkcolorbarswithmallet (2021), which offers that one viable exit from this tyranny of mediated appearances would be to simply smash our way out.

Gregory Kalliche is an artist based in Brooklyn, New York. Recent exhibitions include Fall River Museum of Contemporary Art, Massachusetts; New Museum, New York, Interstate Projects, Brooklyn, and Signal, Brooklyn. Additional projects include 57 Cell, a publication that Kalliche produces featuring 3D-modeled exhibitions in simulated environments, and Pretty Days, an offsite curatorial project he co-runs with artist Harry Gould Harvey IV.

Kristin Walsh is an artist based in New York City. Recent exhibitions include Helena Anrather, New York, Fjord, Philadelphia, Downs & Ross, New York, and Signal, Brooklyn.

The artists would like to extend a special thanks to Kyle Jacques, Vijay Masharani, and Emma Wippermann.